The Missing: the inspiring Australians who went looking for the war dead

19 April 2021

A digital gallery detailing the humanitarian efforts at the end of World War I has been launched by Victorian Collections, celebrating the efforts of women and men who helped Australian families in their quest for knowledge about their missing relatives.

The Missing digital gallery is a collaboration between Associate Professor Fred Cahir, from the School of Arts, film company Wind & Sky Productions, the Australian Red Cross Society and RSL Ballarat. The gallery details the unsung efforts of the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau – and the Australian War Graves Service (AGS).

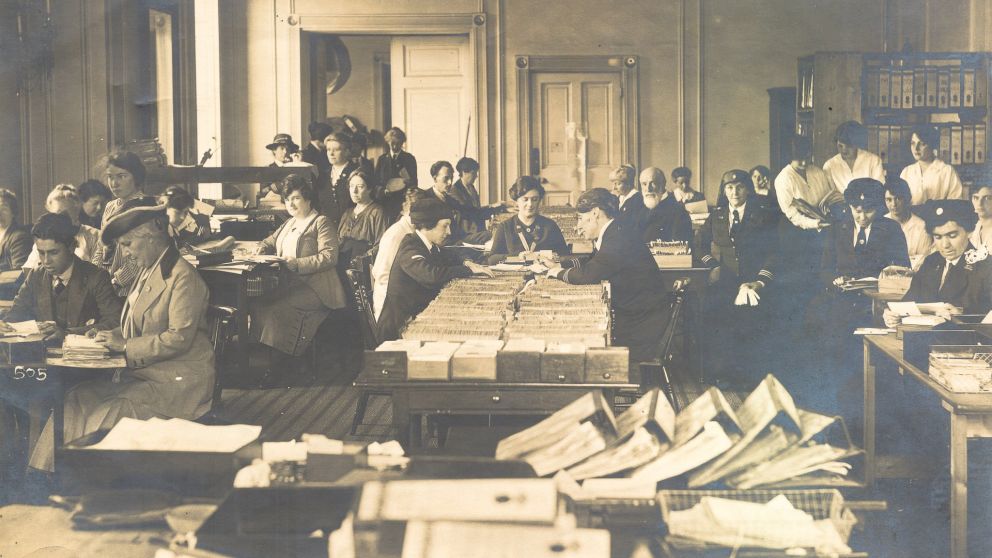

In 1915, the newly formed Australian Red Cross Society set up a volunteer network of information bureaus to help families of missing soldiers discover what had happened to their loved ones. The stories featured in the gallery include the efforts of Vera Deakin, the daughter of former Prime Minister Alfred Deakin, who ran the overseas branch of the Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau – an organisation devoted to finding information on behalf of the relatives of Australian soldiers.

Ms Deakin travelled to Cairo in 1915 before the bureau relocated to London the following year. The demand on the mostly volunteer-run bureau meant that it received up to 25,000 requests for information in one year from Australia.

Lucinda Horrocks, producer at Wind & Sky Productions, has a personal interest in the gallery that she became aware of after learning of Associate Professor Cahir ‘s WWI research. Associate Professor Cahir was researching the role of the AGS after learning his grandfather had stayed behind on Europe’s battlefields after the war.

The AGS, an 1,100-strong group of mostly ex-veterans, stayed behind after the fighting stopped to locate, identify and then rebury the thousands who died. More than 60,000 Australians were killed in the Great War and, more than a century later, 18,000 still have no known grave.

“At the time I was speaking with Fred, I had been researching one of my own family history trails and discovered that my great, great grandmother had lost a son in 1917. He had been recorded as missing and she had sent this poignant series of letters to this inquiry bureau that I had never heard of, saying ‘please find my son – I can't believe he’s dead’,” Ms Horrocks said.

“Those letters were kept in the War Memorial and she had been writing to this person called Vera Deakin.

“So I became interested in finding out more about this group when we realised that there was this great connection between Fred's grandfather and my great-great-grandmother, which is this crisis of the missing in World War I.”

Ms Deakin’s team of forensic clerical detectives would write thousands of letters to Australian families after eyewitnesses who had last seen the missing soldiers had been tracked down.

“Vera Deakin was not the only remarkable woman to volunteer for the Red Cross in WWI. She was one of many women who used their own funds to get to Europe to be involved in the war effort. Some worked in the field, others were back in Australia, collecting information for families desperate for news,” Ms Horrocks said.

“These amazing people in the field were called searchers and they would usually interview two people in the army who had last seen that particular soldier alive. They would fill out a form and send it back to Vera Deakin and her team.” Lucinda Horrocks

“The role became known as tracing – a term that we’re now familiar with in a very different context.”

The letters Ms Deakin’s team sent back to Australia rarely had good news. Missing soldiers were occasionally found recuperating in hospitals or captured as prisoners of war. But mostly these letters informed the family the soldier had died and provided what was known of their final moments – as verified by the eyewitnesses.

The gallery is the second of three projects funded by a Victorian Government grant and includes a series of photo essays written by researchers and those with a personal connection to WWI. It also tells the story of the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne – created to provide a place for people to mourn.

The first project – the documentary film The Missing – was released in November 2019 and was a finalist in the 2020 Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM) Awards. It screened at festivals around Australia and overseas, including the Melbourne Documentary Film Festival, Veterans Film Festival and Ogeechee International History Festival. It featured compositions from Arts Academy Director Associate Professor Rick Chew.

A third component of the project, an education resource kit, is in production and is due to be released in mid-2021.

Related:

The Missing digital gallery

After the war: remembering those who chose to stay behind