The role of Aboriginal knowledge in the defence of Australia during WWII

22 December 2020

As fears grew that an attack on Australia’s mainland by Japanese forces in 1942 was imminent, soldiers from remote regions of northern Australia implored their senior officers to adopt Aboriginal Knowledge – or bushcraft – as a strategic tool to prepare for a land-based invasion.

A few Australian Army officers were aware of the Aboriginal knowledge of food, medicine, signalling and tracking, and the calls went to the top of the command – Prime Minister John Curtin – Australia’s wartime leader.

“While scores of researchers have explored the contribution of Aboriginal people to the World War II effort overall, little is known about the Australian Army’s use of Aboriginal Knowledge – or what is commonly referred to as bushcraft,” Associate Professor in Aboriginal History Fred Cahir said.

Associate Professor Cahir is leading a project to identify the key individuals and their attempts to alert the Australian Army about the advantages of using Aboriginal Knowledge in the event of an attack. The research has been funded with an Australian Army History Unit Grant.

“There were some key individuals particularly in north-west Western Australia where places like Broome and Onslow had been bombed and there was a lot of reconnaissance being made by the Japanese of the coastline, so there was a high degree of anxiety by local army commanders in those regions.”

The anxiety extended across much of northern Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory including Arnhem Land where, for a short period, there was a strong expectation that an invasion was imminent.

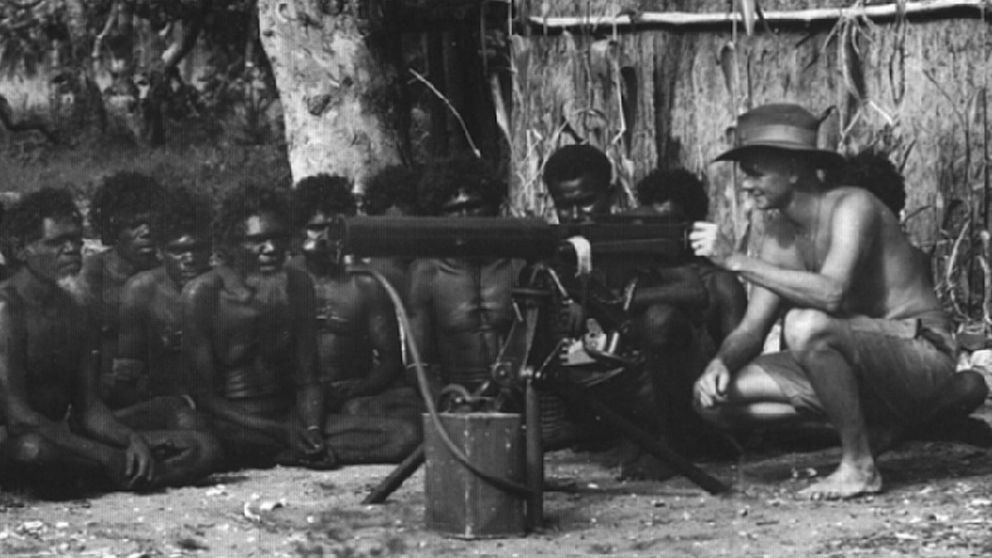

The soldiers who were lobbying their commanders to adopt Aboriginal Knowledge were also eliciting the recruitment of Aboriginal people into the armed forces. The Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit (NTSRU) was an irregular warfare unit of the Australian Army during World War II, composed mainly of Aboriginal people from the Northern Territory. Formed in 1941, the unit patrolled the coast of Arnhem Land during 1942–43 searching for signs of Japanese landings and trained to fight as guerrillas using traditional weapons in the event of an invasion.

Associate Professor Cahir said many non-Aboriginal people who lived in remote regions of Australia had learnt to rely heavily on Aboriginal bushcraft and, with no medical services nearby, many relied upon it for their survival.

“Some Australian Army commanders discovered that Aboriginal people were very skilled at guerrilla tactics and quickly realised that they didn't need to train them a great deal – in fact, quite the opposite. They thought it would be very wise and prudent to enable Aboriginal people to pass on their skills, tracking in particular," Associate Professor Cahir said.

“Being able to find food and water – these were skills that the general army needed in those particular areas if they were going to fight a rearguard action against the Japanese. Several of these commanders were corresponding with Prime Minister Curtin to try and convince him to allow them to use those forces.

“Most people are aware of Indigenous Knowledges, but in general many people have excised the fact that our white pioneers were largely reliant on Indigenous Knowledge to survive in the bush.” Associate Professor Fred Cahir

Perhaps the most significant use of Aboriginal Knowledge in World War II was not in defending Australia, but on the other side of the world and at one of the most pivotal points of the conflict.

In the planning for the D-Day air and sea invasion of German-controlled Normandy in 1944, the Allied forces faced a significant constraint in sourcing anti-seasickness medication, with the standard medication at the time under German control.

“The Allied forces were facing the prospect of more than 156,000 Allied infantrymen with seasickness in what would be the biggest amphibious invasion that had ever occurred,” Associate Professor Cahir said.

“So they looked to other sources and they found an Indigenous medicine, a plant called Duboisia myoporoides, which is a soft corkwood tree, and they quickly got in contact with Australian pharmaceutical companies who were aware of this Indigenous medicine and supplied almost every single Allied soldier that landed on D-Day.”

Associate Professor Cahir will search through archives in Western Australia, Canberra and the Northern Territory to find information on the individuals, and their letters and memos to the Prime Minister and other military leaders urging them to use Aboriginal Knowledge in a more pervasive manner in training.