Comfort from the past: not all is unprecedented

28 October 2020

By Elise Whetter

The term ‘unprecedented’ has frequently emerged during 2020. Unprecedented ecological disasters, unprecedented economic movements, an unprecedented pandemic. Such terms can exacerbate the impact of these events on the wellbeing of individuals, communities and societies.

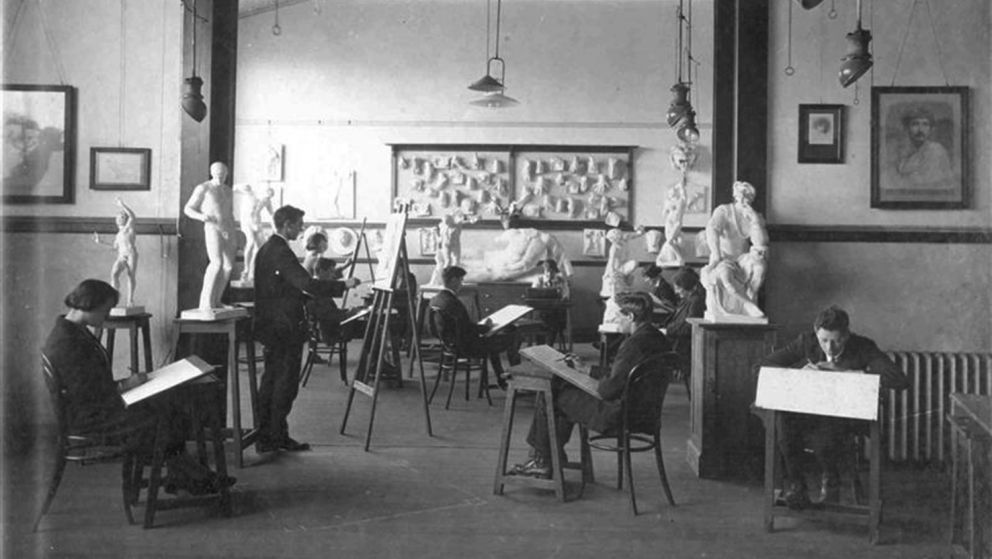

So, it may be comforting to know that such events are not wholly unprecedented. In researching the history of the Ballarat Technical Art School in the first half of the 20th century, the challenges experienced by several student cohorts were not dissimilar to those faced by educational institutions today.

At the end of the 19th century, as local mineral resources dried up, the Ballarat School of Mines and Industries (SMB) sought to diversify its training, adding the amalgamated Ballarat Technical Art School to its masthead from 1907. The school prioritised art teacher training and the application of art to industry and catered to secondary and tertiary students through SMB’s junior and senior schools. The subsidising income of applied art departments enabled the School of Mines to also continue its original remit.

In 1911, the Victorian Education Department felt young people were being drawn into a "butterfly existence", flitting among the many popular amusements available to them. Their levity was thwarted when Australia followed Britain into the First World War, the scale of its horrific consequences perhaps unforeseen by local politicians. A prolonged drought, falling revenue and war-related expenses, saw the state government struggle to fund technical school maintenance.

As many senior male SMB students enlisted, fewer enrolments reduced fee income. The Art School was partially shielded by its large senior female cohort, who undertook war relief and fundraising efforts alongside junior students. Between 1915 and 1918, they bolstered school esprit-de-corps by forming an Art Students’ Club, Reading Club, and Dramatic Society, and participated in inter-school sporting activities.

In 1916, the annual SMB Magazine was relaunched, if imbued with a spectre of grief and loss. Some enlistees did not return, others were incapable of resuming their training. Over the coming years, the Art School benefited from a somewhat perverse boom in commemorative and memorial commissions, and many technical schools received Commonwealth funds to, at least partially, retrain repatriated soldiers.

If a return to post-war ‘normal’ was hoped for, the 1918 influenza pandemic stalled optimism. Attendances slumped as some parents temporarily withdrew students for fear of infection. Where staff became unwell, their duties were covered by overworked colleagues. Almost 20 years later, in 1937, a terrifying outbreak of Infant Paralysis (poliomyelitis) struck Victorian children, resulting in 21-day isolation periods, school closures and state border police patrols. Once again, panicked parents would withdraw their junior technical students from SMB, forgoing certificate examinations and abandoning a year’s work.

Like the COVID-19 pandemic, the Great War highlighted social disparities. It also triggered debate about technical education and training globally, including the importance of training women in fields beyond the domestic economy. Technical art schools were great facilitators of this aim.

A period of relative stability followed Armistice, and students embraced new and pre-war interests and diversions. SMB students revelled in the opportunity to socialise, celebrate and perform; from street parades and fancy-dress follies to understated game nights and elegant balls. They continued to fundraise and volunteer within the community. Meanwhile, the Art School maintained a position of relative advantage until social, administrative and legislative changes affected operations in the late 1920s.

Following the stock market crash of 1929, as livelihoods were lost and studies disrupted, opportunities for celebration were subdued. High unemployment prompted calls for increased training opportunities, but government funds were not forthcoming. As student attendance fell, so did fee income.

Technical schools faced tough decisions, most entering maintenance-only mode with minimum expenditure. Across Victoria, teacher salaries were frozen or reduced, and some were sent on leave without pay. Others were simply relocated by the Education Department. Meanwhile, SMB attempted to alleviate the financial strain experienced by student families, reducing or deferring fees, and the Art School established critical scholarships.

For various reasons, including campaigns to encourage patriotic purchasing of Australian made products, by 1935, record numbers were again enrolling in junior and senior technical classes across Victoria, with the greatest gains experienced in Melbourne. SMB was prepared to train many unemployed, but the Victorian government was reluctant to financially support them. In turn, state administrators urged the Commonwealth to contribute much-needed funds for buildings and equipment, but the request fell on deaf ears.

Undeterred, technical schools modified their courses to suit changing and expanding industrial requirements. At SMB, more students undertook full courses over longer periods, rather than ad-hoc, single subjects. However, by 1939, SMB’s operating council believed itself unsympathetically treated by a state government that favoured Melbourne institutions with a disproportionate stream of funds, and efforts toward administrative centralisation. Many concerns, however, would be overshadowed by a new world war.

In Victoria, at least, educational institutions, teachers and students have overcome historic obstacles. Today, we face uncertain socio-political, economic and environmental challenges, their consequences ranging from inconvenient to catastrophic. While government effort, organisational response, and individual resilience will vary, Victorians demonstrated capacity to collectively withstand challenges is certainly not unprecedented.

Elise Whetter is a PhD candidate in the School of Arts. Elise is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Fee Offset Scholarship through Federation University Australia.